Fallout From Covid-19, Climate Change And Polar Bears

“Economic shutdowns have allowed animals to reclaim the neighboring land. Covid-19 related clean air highlighted climate change and the fate of polar bears. Contrary to media reports and studies, polar bears are not starving and disappearing. ”

During the shutdowns in response to Covid-19, wild animals have taken back the streets of towns and cities, as well as the backyards of homes. We have been following this development via newspapers, magazines and television. We were struck by a news item a week ago citing the increase in the number of bears entering homes in Connecticut. That news got us thinking about the status of the polar bears. Our concern about those bears was raised because of all the recent narratives about global warming and the melting of the ice in the Arctic, and now new studies.

According to the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP), an "unprecedented" number of black bears have entered homes so far this year. Through July 8, the DEEP has received more reports of bears entering homes — 25 — than in any previous year. At this rate, Connecticut would triple the average number of home entries of 2018 and 2019. The scary issue is that the number of home entries reported this June — 17 — equaled those reported during all of 2019.

Exhibit 1. Black Bears Becoming Aggressive SOURCE: DEEP

DEEP officials commented about the rising number of bear home invasions. The increase in year-to-year incidents has resulted in an "unprecedented number of complaints and requests for assistance." Some of these interactions have been serious, as bears entering homes have injured both leashed and unleashed dogs, according to DEEP officials.

A photo from a homeowner in Farmington, Connecticut, shows a mama bear sitting in his backyard, after the homeowner’s dog had sent her two cubs scurrying into a tree for safety. The mama bear then proceeded to enjoy the respite from controlling her cubs and visited the homeowners’ garbage cans.

Exhibit 2. A Black Bear At Home In Back Yard SOURCE: Fox 61, Photo Credit: Casey Howes

We have been fascinated by the photos available on the Internet showing various wild animals taking back cities during the Covid-19 lockdowns. (The Guardian web site has an interesting collection of photos.) As an example, the nearby photo shows mountain goats roaming the streets of Llandudno, Wales, in March. They were drawn into town by the lack of people and tourists. The goat herd normally lives on the rocky, limestone headland of Great Orme, on the northwest coast of Wales, northwest of Llandudno.

Exhibit 3. Wild Animals Reclaim Towns During Virus SOURCE: The Guardian, Photo Credit": Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

The issue of polar bears recently surfaced after the Department of the Interior moved to allow drilling in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). Holding an oil and gas lease sale in the Coastal Plain was mandated by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act enacted in 2017. As part of the leasing process, an environmental assessment must be completed. This report (we haven’t read it) reportedly concluded that drilling activity wouldn’t harm local polar bears. This an entirely different argument than climate change is destroying the Arctic habitat of polar bears, resulting in them becoming extinct.

Democratic members of the House of Representatives’ Natural Resources Committee, wrote to the Interior Department stating that the study “makes the unsupportable conclusion that industrializing the entire Coastal Plain—including the most important terrestrial denning habitat for among the most imperiled polar bear population on the planet—will not jeopardize the survival and recovery of the species.” The letter, authored by Rep. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.), claims, “This fundamentally flawed analysis ignores the overwhelming scientific evidence that identifies devastating impacts to polar bears from oil and gas activities."

Once again, polar bears are becoming a political football. It was only a couple of years ago when National Geographic showed a video of an emaciated polar bear with the enticing title: “This is what climate change looks like.” The video reportedly had 2.5 billion views, and as of today, remains one of the most viewed videos on the magazine’s web site.

Exhibit 4. Devastating Photo Of Polar Bear SOURCE: National Geographic

About a year ago, Michele Moses of The New Yorker magazine wrote a story about the polar bear and why it has become the face of climate change. She told about another emaciated polar bear that showed up in Norilsk, an industrial city in Siberia known for the production of nickel, for the first time since 1977. It rummaged through garbage cans for food and rested in a local sand pit. The assumption was that the polar bear had been forced to travel hundreds of miles to reach Norilsk. Some local environmentalists speculated that the bear’s trip was due to starvation, since melting sea ice forces polar bears to seek other sources of food onshore or go hungry.

A team of specialists examined the polar bear and found that her coat was too clean to have weathered such an extended journey. They thought it possible she had been captured as a cub and raised by nearby poachers. Fearing a recent crackdown on poaching, they released her to stay out of trouble. The specialists have transferred her to a zoo, where she can be cared for and treated for the illnesses contracted by eating garbage.

In the case of the National Geographic story, some scientists accused the organization of being loose with facts. As they pointed out, there was no way of knowing that climate change was the sole cause of the animal’s starvation. The polar bear may have been merely ill or old. In response, National Geographic published an explanation, written by Christina Mittermeier, one of the video creators, titled “Starving-Polar-Bear Photographer Recalls What Went Wrong.” Included in the story was the line: “Perhaps we made a mistake in not telling the full story—that we were looking for a picture that foretold the future and that we didn’t know what had happened to this particular polar bear.” This is another example of activists with a preconceived storyline, never mind seeking the truth.

Since polar bears were placed under the protection of the Endangered Species Act in 2008 over concerns that its Arctic hunting grounds were being reduced by a warming climate, the polar bear population has been stable. In 1984, the polar bear population was estimated at 25,000. By 2008, when polar bears were designated a protected species, The New York Times noted the number remained unchanged: “There are more than 25,000 bears in the Arctic, 15,500 of which roam within Canada’s territory.”

“The State of the Polar Bear Report 2019,” authored by zoologist Dr. Susan Crockford for The Global Warming Policy Foundation, updated the polar bear count, which is complicated by the incomplete data from surveys of regions promised to be conducted by 2019 were not. The introduction begins with the following:

“The US Geological Survey estimated the global population of polar bears at 24,500 in 2005. In 2015, the IUCN Polar Bear Specialist Group estimated the population at 26,000 (range 22,000–31,000) but additional surveys published in 2015–2017 brought the total to near 28,500. How-ever, data published in 2018 brought that number to almost 29,500, with a relatively wide margin of error, and arguably as high as 39,000. This is the highest global estimate since the bears were protected by international treaty in 1973. While potential measurement error, lack of recent surveys, conflicting methodologies, and unpublished data mean it can only be said that the global population has likely been stable since 2005 (but may have increased slightly to moderately), it is far from the precipitous decline polar bear experts expected given summer sea ice levels as low as they have been in recent years.”

One of the great problems about polar bears is that population surveys are covering huge areas. As a result, not every area is surveyed consistently or frequently. This forces the governments in the Arctic to estimate the population. The good news is that the Russian government has indicated it will survey polar bears in its Arctic region in 2021 and 2022.

Exhibit 5. History Of Polar Bear Population Counts SOURCE: Foundation for Economic Education

A study published early this year in Ecological Applications and hyped by CNN, concluded that polar bears are getting thinner and having fewer cubs, all attributed to melting sea ice. According to the study, between 2009 and 2015, polar bears spent an average of 30 more days on land than they had in the 1991-1997 period. That is attributed to sea ice melting faster and earlier in the season than 25 years earlier.

A team of scientist led by Kristin L. Laidre tracked the movements of adult female polar bears in Baffin Bay, a body of water off the west coast of Greenland, over two periods of time in the 1990s and 2010s. The report acknowledged that the last count of polar bears in Baffin Bay was conducted between 2012 and 2013. It estimated the population at over 2,800 then, according to the IUCN Polar Bear Specialist Group. Since there hadn’t been an earlier count, it is difficult to know whether the estimated polar bear population increased or decreased. However, all earlier counts showed an increase or stability in the polar bear population.

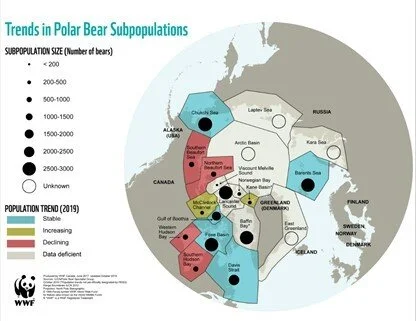

A 2017 map by World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), updated in October 2019, shows the 19 subpopulations of polar bears. The 2019 update stated that the population of polar bears in the Chukchi Sea region had been stable between 2008 and 2016. This was hailed as good news, although WWF also warned that the ice situation there was troubling so this population needed to be watched closely. The Baffin Bay count was for a region with insufficient data to draw any conclusion about the population trend.

Exhibit 6. Graphic Depiction Of Polar Bear Counts SOURCE: WWF

The WWF assessment report suggested that the number of polar bear subpopulations experiencing decreases had increased from one to four. They are noted in red on the map, and are in Canada. Then again, Canada holds 60%-80% of all the polar bears in the Arctic. The report said that the Southern Hudson Bay population dropped by 17% and the Western Hudson Bay population declined by 18% between 2011 and 2016. Given how populations are counted (estimated), we are not sure how accurate the percentage changes are, or if they are significant.

A recent article by polar bear expert Dr. Crockford addressed the health of polar bears amid melting sea ice. She wrote the following dealing with the chart in Exhibit 7 (next page).

“Assuming low summer sea ice like we’ve had for more than the minimum 8 out of the last 10 years, total eradication of Western Hudson Bay polar bears – as well as extirpation of bears in nine other subpopulations, comprising all ‘divergent’ and ‘seasonal’ sea ice ecoregions, as shown below – is what USGS polar bear researcher Steven Amstrup predicted when he and his colleagues filed their reports in 2007 to support listing polar bears as ‘threatened’ under the US Endangered Species Act (Amstrup et al. 2007; Durner et al. 2009). Eradication of those ten subpopulations, the experts said, would cause the global population to decline by 67%.”

Exhibit 7. 2007 Prediction Of Polar Bear Demise SOURCE: US Geophysical Service

According to Dr. Crockford, “In 2007, USGS expert Steven Amstrup predicted that all of the bears in the green and purple regions [Exhibit 7] would be wiped out if sea ice declined to low extents by 2050. However, the ice declined faster than expected – we’ve had that dreaded sea ice future since 2007, and polar bears thrived. None of those 10 subpopulations has disappeared.”

In 2017 and 2019 papers, Dr. Crockford showed the reality of melting sea ice happening well before 2050. Her graph showed the 41-year trend in sea ice extent, as well as the steepest 13-year trend and the flattest 13-year trend. Despite the dire outcome for sea ice extent, the logical conclusion would be polar bear populations would be decimated.

Exhibit 8. Melting Sea Ice Has Already Occurred SOURCE: Dr. Susan Crawford

According to Dr. Crockford, Western Hudson Bay has seen a decline in summer sea ice of 0.86 days per year, one of the smallest declines in sea ice of all polar bear subpopulation regions, which translates to four weeks since 1979. Polar bears in this region now spend up to 5 months onshore in the summer, up from about four months previously. However, it has been acknowledged that this change happened in a single ‘step-change’ in 1995 or 1998, depending on the data used. In other words, there has not been a steady, gradual decline in summer sea ice over time as CO2 has increased. Ice breakup dates from 1995 to 2015 were about two weeks earlier than during the 1980s, while freeze-ups were about a week later, with lots of variability. For the past few years, freeze-ups have been like the 1980s, and this year, breakup is even looking like it did in the 1980s.

Western Hudson Bay polar bear numbers declined 22% between 1987 and 2004, but has been stable since 2001 at about 1,030 bears, even as some polar bear experts continue insisting that they are suffering due to a lack of ice. Data to support claims that Western Hudson Bay polar bears are in poor health (i.e., skinnier) compared to the 1980s, or reproducing poorly have not been published according to Dr. Crockford. On July 15, one of the first bears off the ice in Western Hudson Bay was a fat female and her equally fat cub, as captured on the explore.org live-cam at Wapusk National Park south of Churchill. One of the official moderators commented: “The PBs we’ve seen so far are coming off the ice nice and fat. Seems it’s been a good hunting season for them.”

Just last week, another polar bear study was released via a paper in the journal Nature Climate Change. The conclusion of the study was that polar bears could become nearly extinct by the end of the century as a result of shrinking sea ice if global warming continues unabated. The New York Times article about the study contained the following:

“’There is very little change that polar bears would persist anywhere in the world, except perhaps in the very high Arctic in one small subpopulation’ if green-house-gas emissions continue at so-called business-as-usual levels, said Peter K, Molnar, a research at the University of /Toronto Scarborough and lead author to the study.”

There are several key points about the study and its authors worthy of note. First, the “business-as-usual” greenhouse-gas emissions scenario is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) RCP8.5 climate scenario, which is the most extreme case and one that has been discredited as being totally implausible. Second, the study uses polar bear data collected up to 2009, and only from Western Hudson Bay, which has been acknowledged to be an outlier, to predict the response of polar bears worldwide. The ice-free period for Western Hudson Bay has not continued to decline since 1998 but rather has remained stable (with yearly variation) at about 3 weeks longer than it was in the 1980s, as reported in a 2017 study. More recent data shows further improvement in the ice-free season for Western Hudson Bay bears as discussed above. Not utilizing more recent data raises further questions about the Molnar model. Third, Dr. Molnar is a known polar bear catastrophist, and one of his fellow authors was USGS expert Steven Amstrup, who wrote the 2007 paper (discussed above) predicting the demise of the polar bear population that proved wrong.

The battle over polar bears and melting ice due to climate change will continue. The completion of surveys underway, and hopefully the Russian surveys, will shed more light on the population of polar bears. Barring a significant decimation of one or more subpopulations of polar bears, it is difficult to see anything but a continuation of a stable count. That would appear to fly in the face of forecasts of the extinction of polar bears due to climate change. That reality, however, is likely not to dissuade the continued use of polar bear photos to popularize the climate change case.